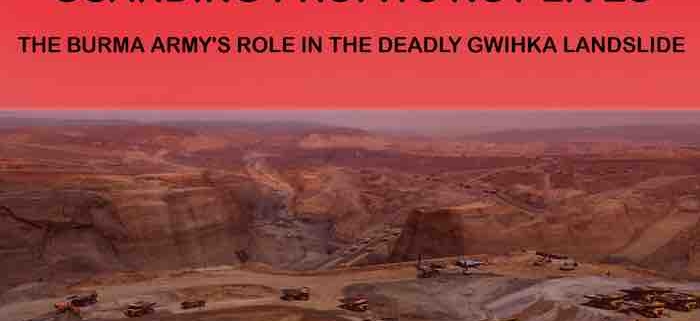

Guarding Profits Not Lives

On July 2, 2020, about 300 mine workers died in a deadly landslide at a jade mine at Gwihka in Hpakant, Kachin State. The casualties were all jade scavengers, working in a mine that was officially closed for the rainy season.

Most media reports have blamed the disaster on poor law enforcement, and on the greed of mining companies, who flouted environmental protection and safety laws, letting their mines become giant death traps. The Union Minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Ohn Win placed blame on the victims themselves, for their “greed,” while State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi blamed the tragedy on joblessness, which drove the scavengers to work “illegally.”

There has been little focus on the Burma Army’s role in the tragedy, beyond mention of their beneficial ownership of many of the jade companies. Indeed, one of the three main companies operating in the Gwihka Mine was the military-owned Yadana Kye, which was using dynamite and heavy machinery to keep digging right until June 25 – when the

mine was officially closed for the rainy season – despite clear signs of instability at the 1,000-foot-high edges of the open pit mine.

But the Burma Army bears responsibility for the disaster in a more direct way. For the Gwihka Mine, like the rest of the Hpakant jade mining area, is under tight control of the government military. Their troops guard all the mining sites, and should have ensured that the unstable Gwihka Mine was out of bounds. The troops did not seal off the mine for the

simple reason that their function was not to secure lives, but to secure profits from the jade extracted – in this case by the scavengers, from whom the military automatically receive a share of profits from any jade found.

The highly lucrative “taxing” of manually scavenged jade is a sizable revenue source for the military, shared up to the highest levels, and collected in cash by troops on the ground — currently the notoriously brutal Infantry Division 33, posted to Hpakant after committing mass atrocities in northern Rakhine in 2017.

For jade scavenging is not, as it appears, an informal free-for-all, but a tightly controlled enterprise, with the main profits going to companies and the military, and only small earnings going to the scavengers themselves.

Scavenging is at the bottom rung of the exploitative supply chain of the jade mining industry, whereby the free labour — and often life — of the scavengers is used to extract the very last ounce of value from the mines.

Download English

Download Burmese